Introduction

Hello Ladies and Gentleman,

This is Rich Soni, and you are listening to Organic Music Now! Episode 4. This Episode is titled 72 on 72, and its a 72 minute episode which will be analyzing the Grateful Dead’s album, Europe ’72.

Into The Rabbit Hole

For the past month or so I have been diving deep into what I call the Rabbit Hole of the Grateful Dead. Its not the first time that I’ve crawled into this Rabbit Hole but its surely the deepest I have gone thus far. The focal point of this journey has been the Europe ’72 album.

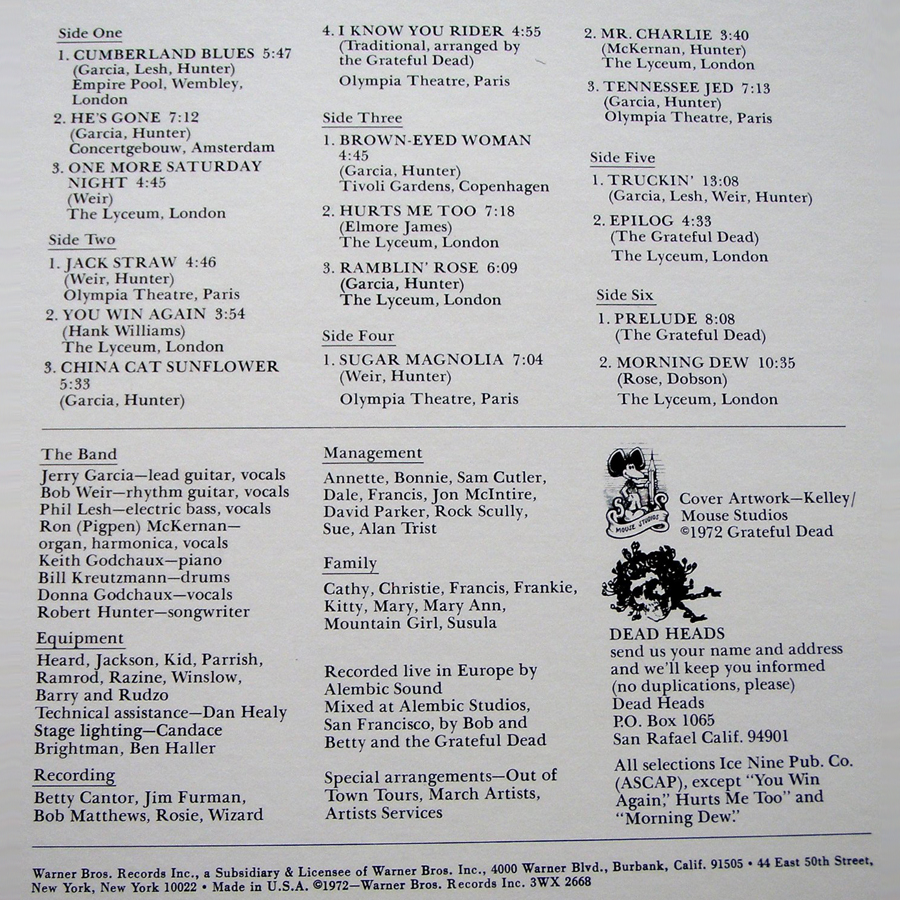

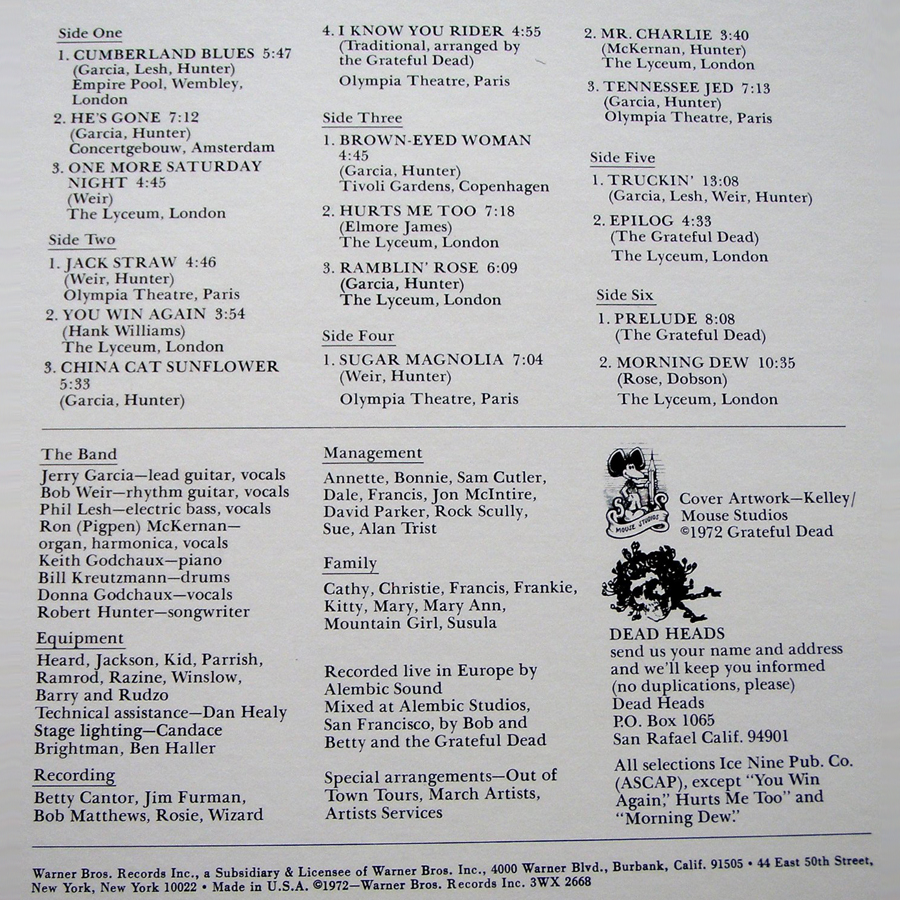

Larger Than A Musical Group

The Grateful Dead something larger than just a musical group, and the Europe 72’ album is representative of this. At every level the Grateful Dead is a cultural organism reflecting a shared set of values. Over the course of this 72 minute adventure, we will visit some of these values, and see how they manifested in the Europe 72’ album, and also how they contribute to the overall aesthetic and philosophy of the Grateful Dead. Our guide on this adventure will be the liner notes for the album, which can be found on jerrygarcia.com/image/europe-72-3/, and they are also listed on the Wikipedia for the album.

The Kickoff Of The Album

Even the first few second of this album is a rabbit hole of information we can gather. We hear bassist, Phil Lesh, kick off a riff in G major. It’s an upbeat & a happy riff. Then we hear Bill Kreutzmann count in on his bass drum and his hi-hat, and Bob Weir slide up into position, then in the background we hear Pigpen and Jerry start to stir the pot a little bit, and soon Phil follows suit, and by now Kreutzmann is grooving, and the band has started playing Cumberland Blues.

Cumberland Blues

Cumberland Blues is the title track on Side Two of 1970 studio release Workingman’s Dead. The song was written by Robert Hunter and Jerry Garcia.

For those of you that don’t know, Robert Hunter was the primary songwriter for the early Grateful Dead music. However, in 1971, Robert Hunter stopped working with Bob Weir, and John Perry Barlow began working with Weir instead, while Hunter still remained working with Jerry.

I have an article on billboard.com from 2015 open, and its titled: Fare Thee Well: Grateful Dead Lyricist Robert Hunter Remembers His Last Conversation with Jerry Garcia. The article itself is an excerpt from an ebook titled: Reckoning: Conversations With the Grateful Dead which is available on Amazon.

In the interview Hunter describes why he stopped writing songs with Bob Weir. This is what he said:

There wasn’t a good close inter-relationship. It’s not Weir’s fault and I don’t think it’s my fault either. It just didn’t quite work. From my perspective, he wasn’t easy to work with. We’d write something and then he would want to rewrite it or add lines, which I didn’t care for. Jerry never did that. He liked what I gave him, and he did it.

Bob and I both tried hard but he didn’t really care so much for hard, elaborate images that I used in songs. He wanted the songs to say something simpler. He voiced that. I said, “That’s what everybody writes. My own style is what I write.”

There are some songs that Weir and I did that worked darn well: “Playing in the Band,” for instance. But we would sometimes work really, really hard only to have what we did disappear, which was frustrating. Like I remember working for days on a song, and then he didn’t like it and called his friend Barlow in. Barlow wrote the words for “Cassidy,” which is a beautiful and classic song, so I had no problem with him at all, but… I think he found it easier to work with Barlow, and with my blessing that’s what he did.

Thats the end of the quote. So, like I said Robert Hunter and Jerry Garcia wrote Cumberland Blues. In the liner notes for the Box of Rain the Grateful Dead Boxed Set, Hunter recounts the best compliment he ever got for a lyric:

from a miner who had worked the Cumberland lode. Hearing "Cumberland Blues," the old miner said, "I wonder what the guy who wrote this song would've thought if he'd ever known something like the Grateful Dead was gonna do it?

The Ripple Effect

This compliment, even if its a myth, says a lot about Hunter as a songwriter, and a lot about the song Cumberland Blues itself. Hunter’s songwriting was tapped into something I call the Ripple Effect. The title being an homage to the Hunter/Garcia song Ripple. The song Ripple is the title track on side two of the other 1970 Grateful Dead studio release, American Beauty. Ripple is followed by Brokedown Palace.

Fare you well, my honey, fare you well my only true one

That first line Brokedown Palace begins with the line ‘Fare you well, my honey, fare you well my only true one’. A line borrowed from the folk canon. A line I knew from the traditional ballad Dinks Song, which I was performing myself when I first heard Brokedown Palace. I myself had learned this song from Jeff Buckley. A little bit later I would rediscover this song on Volume 7 of Bob Dylan’s bootleg series, and on his Witmark Demos bootleg series I would also discover another song ‘Fare Thee Well’ which is also reminiscent.

So these ‘hand me down’ lines that we can hear in Brokedown Palace are very representative of this Ripple Effect that I am talking about which is explored much more bluntly and completely in the songwriting of the Terrapin Station Suite, but it can also be seen sweeping throughout all of Hunter’s songwriting. Especially those performed by Garcia in 1972 on the Europe 72’ album.

So just one more thing on the Ripple Effect for now, and we will get back into Europe 72’, its going to kind of lend itself naturally into going back there. I have another article open: Robert Hunter on Grateful Dead's Early Days, Wild Tours, 'Sacred' Songs 2015 Rolling Stone

The interview question he was asked was:

How about a favorite lyric or line you wrote? Let it be known there is a fountain that was not made by the hands of men" [from "Ripple"]. That's pretty much my favorite line I ever wrote, that's ever popped into my head. And I believe it, you know?

Just before that line, in Ripple, he also wrote “Reach out your hand if your cup be empty, If your cup is full may it be again”. The inspiration he draws from, that he said in that quote ‘pops into his head is from something greater’. Something he believes in. Take ‘Fare you well’ for example, That line appeared in Brokedown Palace, and in Dink’s song. It also appears in a song famously performed by Frank Hutchinson called Cumberland Gap.

Im getting homesick fare thee well ~ Cumberland Gap

Even in 1929 this ‘Ripple Effect’ ‘hand me down’ line songwriting method is being used as can be seen with Frank Hutchinson. Frank Hutchinson also famously recorded ‘Stackalee’ which is featured Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. Stackalee is a song that has a very large ‘Ripple Effect’ within music. You will hear it many different songs, the story of Stackalee or references to it. Just one off the top of my head is ‘Wrong Em’ Boyo’ By The Clash on their album London Calling.

Back to Frank Hutchinson and the Cumberland Gap, It has a chorus: “Cumberland Gap, she ain’t my home, I’m a-gonna leave old Cumberland alone”. Compared to the first lines of Cumberland Blues which read: “I can't stay much longer, Melinda The sun is getting high”. Comparing those two lines. We see the similarities between them. This is especially true when looking at the characteristics each of the songs wider lyrical offering of each of the song: There is a miner in each who lives in Cumberland, and although they spend a lot of time in the mine, they want to leave.

One note about the ‘Ripple Effect’ especially in Robert Hunter’s songwriting, is that it is not a ripoff of the other work. Even in Cumberland Blues, there are other ‘Ripples’, for example: ‘I can’t help you with your troubles if you won’t help with mine’, which is reminiscent of another Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music recorded by Dock Boggs which is Country Blues the lines read: I wrote my woman a letter good people, I told her I’s in jail. She wrote me back an answer saying “Honey I’m-a coming to go your bail”.

Whats important to note about these two sets of lyrics, which that they are both related to each other, and the first is a ‘Ripple’ of the second. However, the women being talked about are opposites. The Country Blues woman helping with the trouble. And, the Cumberland Blues woman does not help with the trouble. Its important to note that the Country Blues woman is not the norm in the traditional story within the folk cannon, yet the Cumberland Blues is.

This helping woman theme comes up in other songs such as Goin’ to Germany by Gus Cannons Jug Stomers. Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music features two other Gus Cannon songs: Feather Bed, and Minglewood Blues. Minglewood Blues being the predecessor to New Minglewood Blues. And the Grateful Dead covered this song throughout their entire career.

Cannon’s Jug Stompers recorded another song Viola Lee Blues, which the Dead also covered in their early career.

They also release a song called Goin’ To Germany which Cumberland Blues borrows from the lyric. Here is a lyric from Goin’ To Germany: ‘When you’s in trouble I worked and payed your fine. Now I’m just troubled, you don’t pay me no mind’. Which essentially the same as the line from Cumberland Blues: I can’t help you with your trouble if you won’t help with mine. Another similarity is the plots are essentially the same. Goin’ To Germany being about someone who is going to germany that says: I’ll be back some old day. Just like Cumberland Gap, this line contradicts the message in Cumberland Blues which ends with: ‘I don’t know now, I just don’t know if I’m coming back again.’

This is how Robert Hunter was writing songs, he was really exploring the world of these miners, and of these folk musicians, and understanding what it was like to be them. This is what he believed in this ‘Ripple Effect’, this is where he drew his inspiration from, so if you go back to that quote I read before when Hunter recounts his best compliment that he ever got for a lyric:

from a miner who had worked the Cumberland lode. Hearing "Cumberland Blues," the old miner said, "I wonder what the guy who wrote this song would've thought if he'd ever known something like the Grateful Dead was gonna do it? ~ Robert Hunter on Grateful Dead's Early Days, Wild Tours, 'Sacred' Songs 2015 Rolling Stone

This is the greatest compliment to Hunter because he was trying to use these ‘hand me down’ lines from people like Frank Hutchinson who actually was a coal miner, and he convincingly did it. And, a coal miner believed that song was written by someone like Frank Hutchinson. Which shows this sort of the completion of the Ripple. That’s why it was the best compliment Robert Hunter ever received: because Cumberland Blues was such an authentic coal miner song.

And just a little fun observation: the guy said, "I wonder what the guy who wrote this song would've thought if he'd ever known something like the Grateful Dead was gonna do it?” Obviously, Robert Hunter knew exactly what the person would have thought because he was the person that wrote it. And, he would have thought that it was amazing that he wrote an authentic song that tricked a coal miner into thinking the song was actually from his region about a coal miner in that region.

Hunter In The Band

I want to just pause here, and go back to something that I mentioned early on in the podcast: The Grateful Dead is more than just a band. This can already be seen by looking at the songwriting of Robert Hunter, when you consider his standing within the band. The Grateful Dead is more than just a band. They include Robert Hunter as a defacto member of the band. There is a website dead.net that has a lot of great material on the Grateful Dead, and one of the sections they have lists descriptions of various people associated with the band. There is one for Robert Hunter which gives a good idea for what I mean:

Robert Hunter joined the Grateful Dead in the fall of 1967, when he arrived at a rehearsal just in time to write the first verse of the band's classic "Dark Star." Though he'd never play onstage, he became not only a genuine band member but its secret Ace in the hole. Though Bob Weir's words for "The Other One" would endure, most of the band's early verbal efforts would not; it was Hunter's work that would elevate their songs from ditties to rich, complete stories set to song. Hunter had fallen into the Dead's general scene in 1961 when he'd met Garcia in Palo Alto, and he'd played in several of Garcia's early bluegrass bands. But he'd always thought of himself as a writer -- probably a novelist -- and it was only in 1967 that he fulfilled his personal destiny, and enriched the Dead's. He's gone on to write several books of poetry, and is currently at work on a novel. ~ dead.net

My favorite little quote from it is Hunter is considered a genuine band member. They call him “their secret Ace in the hole.” This is not common for a normal band, that is to have a ‘secret ace in the hole’ songwriter, that is considered a member of the band, but in fact there is something supplemental to the band that makes it something bigger than a band itself.

Liner Notes: The Band

So, I mentioned in the beginning, that the liner notes for the Europe 72’ album would be the guide. Placing where we have gone so far, we can see Robert Hunter as songwriter listed beneath the band section of the personnel listing. Which shows that The Grateful Dead is not the typical band. There is something more to it than just a typical band. There also is a typical list of usual suspects:

- Jerry Garcia - lead guitar, vocals

- Bob Weir - rhythm guitar, vocals

- Phil Lesh - electric bass, vocals

- Ron (Pigpen) McKernan - organ, harmonica, vocals

- Bill Kreuzmann - drums

Where is Micky Hart?

We have the notable absence of drummer Mickey Hart from the liner notes. Hart and Kreuzmann had been the drumming duo which gave the dead their punch since Kreuzmann met Hart in 1967 and invited him to join the band soon after.

In Phil Lesh’s book Searching For Sound, he speaks of Harts departure:

He says,

Mickey had been sinking into a terrible depression.

He also says,

he decided to leave the road — never a favorite part of it for him — and work out his destiny at home on his ranch, with the explicit understanding that he was more than welcome anytime he wanted to rejoin us, wherever we were.

Harts father, Lenny, had been the manager of the band, and was recently fired and being sued by the Grateful Dead. This was the driving force of Mickey Harts depression.. Was was also a great source of stress for both Hart and the rest of the Grateful Dead. Here is an article from 1971 titled Lenny Hart Arrested:

August 1971: Lenny Hart Arrested

GRATEFUL DEAD BUST THEIR DAD

SAN FRANCISCO - The Grateful Dead have found and busted Lenny Hart, their elusive former manager and the father of ex-drummer Mickey Hart. He was in San Diego, the Dead said - baptizing Jesus freaks under the name and title with which he had first approached the band two years ago: The Reverend Lenny B. Hart.

A warrant had been out, and a suit filed, for Hart since he split in spring last year. The charge, said Dead accountant David Parker, was embezzlement. Hart was found by private detectives two weeks ago, according to Rock Scully, and spent a weekend in jail. Bail was set at $38,500; Hart reportedly bailed himself out.

Various members of the Dead organization tried to piece the father-and-band association together. "He had come to us as a man of God," said Scully, who left the Dead while Lenny Hart was there. "He said, 'You've been fucked around. Now, I don't ask you to believe in Jesus, but believe in me. Fill the vessel!' You know, 'The content's beautiful but we've got to hold it!' He really cleaned the hell out of all of us."

Parker joined the band's office around the time of Hart's departure, in March, 1970. "It became obvious to everyone - something was strange," he said. "He wouldn't hand over the checkbook or let us look at the books. There were several confrontations with a number of people; we were going to file suit.

"Then he got a lawyer and said he'd pay the money back. $70,000 was the amount we put down for suit; that was the amount clearly beyond a doubt that had been dealt with in a suspicious way. It may have been double that, we didn't know. He promised to pay, put down $10,000, and split. He cleaned out all the bank accounts, and the band didn't even have any money to go on the road with."

"When he ran off on us," said Scully, "he'd just gone to L.A. with Garcia to negotiate for music in Zabriskie Point. Well, he just took the check and split. We found out he had 11 accounts spread out through California. He'd open up 'new companies' and put the money there." The band, he said, thought Hart was putting aside money to pay taxes. "You know how you save to avoid getting hit at the end of the year? Well, we got hit."

Manager John McIntire shook his head. "So much of it's so cut and dry it's amazing how stupid we were," he said. "It was a classic trip: Elmer Gantry coming in. We deserved it. But you wouldn't think he'd fuck his own kid."

Mickey Hart left the band shortly after his father had split. "Mickey's still reacting to it," said Scully. "I mean, he was burned by his father."Track 2 of Europe 72’, ‘He’s Gone’ chronicles the departure of Lenny Hart from the band. David Dodd explains this on his website, The Annotated Dead:

"He's Gone," as originally written, referred to the disappearance of Mickey Hart's father, Lenny Hart, who was acting as the band's manager, with a good deal of money. (See interview in Relix, vol. 5, #2, p. 24.) Since then, the song has become riddled with meaning, played often quite tenderly when someone close to the band dies.

The band repurposes the song throughout their career, but its interesting because the absence of Hart from the liner notes is reflected back into the music that the Grateful Dead was playing.

Heres a couple of lines that give the tone as they said, the song is riddled with meaning, but they do reflect the story of Lenny Hart’s departure.

Rat in a drain ditch caught on a limb You know better but I know him

Like I told you What I said Steal your face right off your head

Now He’s Gone Lord He’s Gone

Donna & Keith

That explains the absence of Mickey Hart & Lenny Hart from the liner notes. The remaining two members are Keith and Donna Godchaux which recently joined the band. First Keith then Donna shortly after.

Phil Lesh describes their initiation within Searching for the Sound. He mentions that Donna initially introduced herself to Jerry, pointed to Keith, and said ‘this is your piano player’. Jerry brought Keith to practice one day and Phil describes the the practice:

“there’s Keith at the keys, with Jerry sporting his Cheshire Cat– that-ate-the-canary grin. Introductions were made all around. All through the afternoon we played a whole raft of Grateful Dead tunes, old and new. That whole day, Keith never put a foot (or a finger) wrong. Even though he’d never played any Grateful Dead tunes before, his consummate musicianship and superb training allowed him to pick up the songs practically the first time through. That’s something that we could have expected, but what amazed us most was that everything he played fit perfectly in the spaces between the parts played by the rest of the band. Since Mickey’s departure, we’d been struggling to redefine our nature, to fill in the hole that he’d left— and Keith turned out to be the missing piece.’

In Searching for the Sound, Phil also describes how Donna fit into the mix:

Singing high harmonies was starting to irritate my throat, so during a series of gigs in late March we invited Keith’s wife, Donna, to sing with the band, and we had a new band member.”

Donna was no scrub, its not like they just picked her because she was Keith’s wife. In fact she had been been a session singer in Muscle Shoals before joining the band. Muscle Shoals is renowned for its session musicians specifically a group known as the Muscle Shoals Swampers.

Lynyrd Skynyrd describes them best in the lyrics to Sweet Home Alabama:

They sing Now, Muscle Shoals has go the Swampers And they’ve been know to pick a song or two Lord, they get me off so much They can pick me up when I’m feeling blue

Some songs the Swampers recorded are:

- Respect by Aretha Franklin

- Mustang Sally by Wilson Pickett

- I’ll Take You There by the Staple Singers

- Old Time Rock & Roll by Bob Seger

- Kodachrome by Paul Simon

- When A Man Loves A Woman by Percy Sledge

The last of which features Donna as a backup singer.

I watched a really good documentary on Muscle Shoals on Netflix, and I recommend that you watch it. They get into the Muscle Shoals Swampers, the area, recording Sticky Fingers by the Rolling Stones. Its a great documentary and I suggest you check it out if you have not already.

Donna and Keith had both been with the band for less than a year, Keith’s first show being October 19, 1971 and Donna’s December 31, 1971. So, this is really the first major tour they are on with the Grateful Dead, the 72’ set.

Liner Notes: The Extended Family

So, besides the seven performers and Hunter who occupy the Band section of the liner notes, there are also 35 other people listed on the inside cover of the Europe 72’ album.

The Grateful Dead refer to these people as The Extended Family, it is was I previously described as a loosely formed artistic collective surrounding the band.

Alan Trist & Sam Cutler

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/A-1835966-1488573995-7664.jpeg.jpg)

Several of these extended family members comment on Europe 72’ tour in the documentary series Long Strange Trip, which I watched on Amazon Video and highly recommend, I cannot remember if I purchased it or if its available to stream with Prime but either way its worth it.

Alan Trist and Sam Cutler give contrasting perspectives of the Grateful Dead’s business practices in this one scene of Long Strange Trip.

Trist having the perspective of a romance fueled, scrappy hustler trying to redefine culture:

I was brought in to manage the publishing company, but our roles within the Grateful Dead family actually overlapped you know? We all did a little bit of everything. Your are dealing with a collective, these are not music business professionals. Everybody had a voice, and all voices where listened to. It had the characteristics of an open system. One that cared a lot about the employees ~ Alan Trist

On the other hand, Sam Cutler only served a short tenure as tour manager for the Grateful Dead. Sam Cutler having previously worked with more traditionally structured acts like the Rolling Stones, did not see the romance in the Grateful Dead’s approach to business.

In Long Strange Trip, Sam Cutler shares his experience working with the Grateful Dead:

The Grateful Dead are dumb. They make fabulous music, wonderful, amazing the best music of any band I’ve ever been involved with, fabulous. But when it comes to making business decisions… stupid. It was a nightmare, first off they didnt know how to make decisions. When I first went to a meeting with The Grateful Dead there was all these people there. There was so many fucking people it was ridiculous. They where all part of this amorphous blob of people called the Family. I don’t deal with families I deal with rock & roll bands you know. ~ Sam Cutler

For better or worse though, the reality was The Grateful Dead, had always been and would always be more than just a band. It was baked into the DNA of the whole thing since the very beginning. The reason this crazy thing worked is because The Grateful Dead legacy was much more than a musical offering. Each craftsman involved aspired to disrupt the industry in which they mastered.

Owsley 'Bear' Stanley

Speaking of disruptors, I would like to mention one family member who is missing from the Europe 72’ liner notes, but is perhaps the most famous family member of them all: Owsley “Bear” Stanley. Owsley 'Bear' Stanley was in charge of live sound and recording for the Grateful Dead. In Long Strange Trip, Phil Lesh describes Owsley 'Bear' Stanley as a ‘a mad scientist. a little bit of a mad scientist among many other aspects’. Long Strange Trip has a great segment on Owsley, which I highly recommend. Its probably one of my favorite segments in the entire Long Strange Trip series.

I first heard about Owsley 'Bear' Stanley in the book titled Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties and Beyond. I read this book years ago, even before I got into the Grateful Dead, so my memory of it is is a little vague, and I don’t have the book handy but I can say it conveyed the following for sure: Owsley 'Bear' Stanley made acid and he made it well.

In Long Strange Trip, Steve Parrish, confirmed this supposition. Saying: “(Owsley) made probably the best LSD that has ever been made.” What did not sink in when I read Acid Dreams, was another quote in Long Strange Trip which Steve Parish said, “When the Grateful Dead started, Owsley bought them all of their own equipment, with his Acid Money.” In exchange, Owsley was granted permission to dedicate a significant portion of his life to perfecting delivery of sound at Grateful Dead performances.

In Long Strange Trip, Phil Lesh said, “Bear’s dream was to have a system that you could hear for a mile, no distortion between the string and the speaker, that was his holy grail. At first that was just a fantasy. But then Owsley 'Bear' Stanley started seriously thinking about how it could be done.”

In 1970, Owsley 'Bear' Stanley co-founded a sound equipment company called Alembic, named after an alchemic still. An alchemist used the alembic to distill chemicals apart. The liner notes for Europe 72’ credit this company, Alembic, to the recording and mixing of the music, yet Owsley 'Bear' Stanley has no credit, while others associated with Alembic do.

In Stanley’s NY Times obituary they note: ‘In 1970, after a judge revoked Mr. Stanley’s bail from a 1967 arrest, he served two years in federal prison.’ When Stanley's two years sentence was up in late 1972, he would resume collaboration with The Grateful Dead, but he would not be present for the Europe 72’ tour.

While in Jail, Owsley 'Bear' Stanley learned the trade of metal working and jewelry making. He also considered himself an artist, if you go to his website, thebear.org, you will see his artwork prominently displayed on the page. His artwork was very influential on The Grateful Dead’s popular iconography. In 1973, an album was released called History of the Grateful Dead, Volume One (Bear’s Choice), which was an album curated by Owsley 'Bear' Stanley. The album cover flourish es a ‘Steal Your Face’, the famous Skull and Lightning bolt logo designed by Owsley 'Bear' Stanley as a stencil for marking road gear. Little did he know it would become the most famous logo or icon associated with the Grateful Dead. The back of this album premiered the famous ‘Dancing bears’ logo, obviously symbolizing Owsley.

There is an article from 2005 on deadessays.blogspot.com titled Bear at the Board. There are a few really interesting passages in this article. One of my favorites being the one which Owsley chronicles the circumstances which lead to him joining the Dead family.

“The next time I saw them was at the Fillmore Acid Test, and I met Phil. I walked over to him and said, 'I'd like to work for you guys.' Because I had decided that this was the most amazing thing I'd ever run into. And he said, 'We don't have a manager.' I said, 'I don't think I want to be the manager.' He said, 'Well, we don't have a soundman.' And I said, 'Well, I don't know anything about that either, but I guess I could probably learn.'"

So, the band welcomed in Owsley 'Bear' Stanley, and the conventional narrative typically jumps right to 1974’s ‘Wall of Sound’ period, the Golden Era of the Owsley 'Bear' Stanley / Grateful Dead live sound collaboration. And, this is a natural place to jump if you looking at the overall history of The Grateful Dead.

But, what I like about this Bear at the Board article, is that it tells a more complete story, and includes details about tension’s between Owsley 'Bear' Stanley and the Band which I previously was unaware of.

First they present Jerry’s perspective on the tension:

Aside from taping the Dead, Owsley 'Bear' Stanley was also building a new sound system for them (with Tim Scully), which unfortunately turned out to be unwieldy & unreliable. As Garcia said: "We spent five hours setting up and five hours breaking down every time we played. Our hands were breaking and we were getting miserable, and the stuff never worked... Then we went to Vancouver, and that was the downfall... It was lousy, it was just bad...then we had to work until dawn to pack it up... We decided to disassociate from [Bear's] benevolence and his experiment." ~ Bear at the Board

Then they provide Bear's perspective:

"They decided that the system that Tim Scully and I built was too clumsy and wasn't doing what they wanted. So they wanted to go back to using standard amplifiers. I said, 'Go pick out any amps you want'...they did, and I ended up giving most of the old stuff away. By then I was out of money, so I went off."

That was in 1966, and by 1968 Owsley 'Bear' Stanley was back with the band, they made up their differences and joined forces once again, and remained so until he went to prison in 1970.

When Owsley 'Bear' Stanley got out of jail and returned to the band in late 1972, he was faced with lots of operational and personnel changes to the band. The Grateful Dead went through a period of hyper growth and change in 1971/1972. Lots of this is attributed to the successful reception of Workingman’s Dead, and American Beauty. The Dead’s record label at the time, Warner Music was willing to invest more in the band, and the Europe 72’ tour is the result of that investment.

As such, the liner notes are a Rosetta Stone for understanding this period of great change and growth in Grateful Dead history.

Owsley 'Bear' Stanley was gone for this entire period of Hyper growth and change, and he was faced with it when he returned. The article ‘Bear at the Board’ comments on his experience:

"I came back to a crew that was totally different when I left, and the job that I had been doing was split up amongst three other people, none of whom were willing to yield the territory. I met a lot of resistance in the scene, and after you spend a couple of years locked up, your social adaptability is not very good." ~ Bear at the Board

He continued,

"I found that the three things I did - recording, stage monitors, house mixing - there were three guys doing that! Each one fiercely defending his little territory. 'That's my job, that's your job'... There was a lot of cocaine and a lot of beer, and they were bitching at each other, and everything else. Lots of power trips. I was feeling very uncomfortable.” ~ Bear at the Board

The articles author comments on this period:

Bear has talked a lot about his mixed feelings, coming back to the band in '72 and seeing a big difference in their approach since the freewheeling acid days. After all, they'd spent two years becoming more 'professional', more people had joined the crew, and the scene was not as welcoming to him as he expected. He found that the soundcrew was, as he put it, compartmentalized & territorial, everyone doing their separate jobs - he felt they didn't work as a team anymore, and the crew certainly didn't welcome him back. (And, Bear being Bear, he also felt he could do their jobs better than they could! Often his comments boil down to, 'I tried to tell them how to get better sound but they were too pigheaded to listen...' The guy was/is a cantankerous control freak, with wide-eyed dreams hard to achieve in reality, and probably more difficult to work with than he realizes.) ~ Bear at the Board

Although the author of Bear at the Board puts it rather harshly, I agree with his statement. The Grateful Dead had outgrown their ‘freewheeling acid days’, and was sporting a new level of professionalism in 1972.

Kidd Candelario

Take Kidd Candelario for example. Candelario is the third name listed in the equipment section of Europe 72’.

Bear at the Board says of Kidd:

The Europe '72 tour, was perhaps his taping debut - remember, this is on top of the duplicate tapes that Betty made! "Bob and Betty were out recording that whole tour. I still recorded, but it was just a secondary, cause they had multitracks going... Phil got tapes from me, Jerry got tapes from me, and anybody else who really wanted them. I had to make copies every night for everybody - all of the band members.”

“I wasn't taping for the sake of taping, but only so that the band could listen to the tapes later on. I was either working with Keith or Phil's bass. Sometimes if I wasn't doing anything, I could listen to the taping, and this allowed me to hear problems that were happening, like a blown speaker or something wrong with someone's pickup. So lots of times I'd have to run back and fix something, which meant the tape might run out while I was away from it. This accounts for many of the cuts and missing music out there. But then there's always the problem of when to change the tape... ~ Bear at the Board

As mentioned, 1972 was perhaps Kidd’s taping debut. But it also describes his previous involvement with the band:

Kidd was an old roadie who'd been with the band since the Carousel days in early '68. (In fact, quite a few of the Dead's sound crew - Bear, Bob, Betty, and Kidd - had worked at the Carousel then; and by '72, with Healy now in the crew as well, there must have been quite a crowd behind the soundboard! ~ Bear at the Board

As it stated, Kidd started as a roadie, but in ’72 he joined the sound crew. Kidd was not the only addition to the sound crew in 1972. Bear at the Board three other personnel changes to the sound crew in 1972: Dan Healy, Bob Matthews, and Betty Cantor. All who had a change in responsibilities within 1972.

Dan Healy

Bear at the Board mentioned Dan Healy’s addition to the crew, and describes his beginnings:

Dan Healy became the soundman in '66 after Bear left ~ Bear at the Board

And if you recall, we discussed Owsley 'Bear' Stanley’s absence from 1966-1968 earlier in the podcast, due to feuds with the band around sound equipment.

Bear at the Board continues on Healy:

he had been working in a studio and was friends with Quicksilver Messenger Service. As Bear has said, "Healy is a very pragmatic kind of guy who liked to tinker with stuff and fix stuff...he was a consummate troubleshooter." When he first saw the Dead, not only did he fix a broken bass amp on the spot, he told them their speakers sucked and built a better sound system for their next show. The Dead were thrilled with his ability, and immediately hired him. He recorded and helped mix the Anthem of the Sun shows in early '68, but that was strictly for the album - at the time, he didn't record any other Dead shows, and seems to have discouraged anyone else from recording them. (Which accounts for so few Dead shows surviving from '67.)

The article continues:

From Jan/Feb '68, we have lots of 2-track reels from Healy's recordings that give a fairly complete picture of that tour - the trouble is the Dead did so much chopping-up in the studio, stray reels were left here & there, and a bunch of shows are lost. The new Road Trips snippets came from a couple mix compilations had been abandoned at a studio that was closing. Short of another miracle find like that, we're not likely to hear more new shows from '68. (I think it's possible the "lost" shows from that tour were already lost or discarded as useless by the time they mixed the album, as none of them are on the official Anthem "live tracks" list.)

To add a little more color to the personality of Dan Healy, I found a podcast interview with Healy on The Jake Feinberg Show, here are a few quotes:

One of the first things I noticed was hearing the music and hearing the way it turned out was I discovered that I had the ability to translate the music in our heads into the mechanical equipment

I wound up spending my life kind of helping other people play music, and helping the audience hearing the music we hear in our heads. Jerry Garcia probably was the guy that recognized that I had been given a gift of the ability to translate into the equipment the emotions and the thoughts and the sounds of our music. He was the first one that challenged me to get into that side of it.

He talked about the Beat’s influence on the Grateful Dead scene:

You heard the phrase ‘Rebel without a cause’, we where ‘Rebels with a cause’, our cause was music

The beats goal was to change society, our goal was to play music. It dovetailed because we shared the same audience. Stanley Mouse Pinstriped cars in the late 50s’ and early 60s’. When this all began to happen, they got involved in making posters, and did what has now become fantastically famous art. We coexisted in the same area and same place, and some of our experiences over lapped each other.

He talked about Jerry Garcia, and his role within the band:

Jerry Garcia put his foot down and kept the door open for creativity. He kept the bean counters and legal beagles at bay.

Sam Cutler was not good for the Grateful Dead. It took a long time to get past that.

By 1970 we had milked every drop of innovation. Wall of Sound was a breadboard, and could be configured into any conceivable way.

Candace Brightman was probably very likely the most fantastic greatest lighting director that ever walked the face of the earth. SO, the grateful dead had the best lights and the best sound, and there has been times when Candice and I and the band would collaborate and mesmerize the audience completely.

So those are just a couple rapid fire quotes from that podcast, again if you would like to learn more about Healy I highly recommend you check that out.

So, back to the idea of the hyper growth time for the Dead. I was talking about Kidd Candelario before Healy. I had the quote that read:

Kidd was an old roadie who'd been with the band since the Carousel days in early '68. (In fact, quite a few of the Dead's sound crew - Bear, Bob, Betty, and Kidd - had worked at the Carousel then;

I would love to get into Carousel, but I am running out of time. I am going to have a Volume 2. of this podcast, so I will include that information in there. There was a good bit of information on the Carousel in the Jake Feinberg Show podcast with Dan Healy.

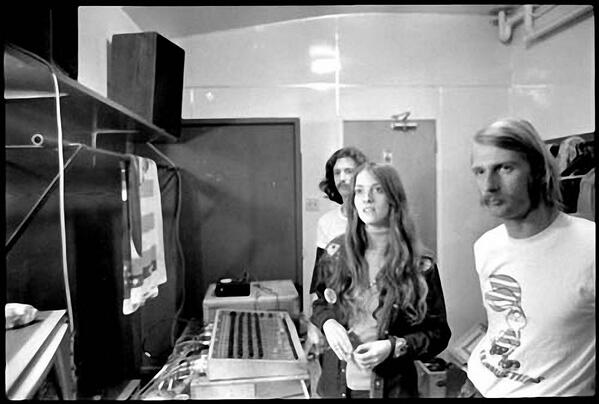

Bob Matthews and Betty Cantor

As mentioned above, Bob and Betty worked at the Carousel with Kidd. We can get into the Carousel later if there is time. They also where mentioned to have been recording the whole tour in multitrack. Here is some more specifics from Bear at The Board:

Bob Matthews, a Dead hand from their early days, and his assistant Betty Cantor. It's worth saying a few words about them - Betty started out working at the Avalon, where Bob Cohen was the recording engineer who taped many of the bands there, including the Dead. (He taped the September '66 show we have, for instance; but other shows were lost or erased.) She went to work at the Carousel in '68, and became involved with Bob Matthews there. He'd been on the Dead's equipment crew in '67, and when he became a recording tech, he lured her with him: "It was my way of getting her to be my old lady." They started out recording the Dead by working on Aoxomoxoa in the studio; recorded and mixed the Live/Dead multitracks; and the next year produced Workingman's Dead. At first Betty was mainly Bob's clerical assistant, but through '69 she started working more on mixing and editing tapes. At that point she didn't usually go on tours, staying in the studio - later on she and Bob taped the multitracks for Skullfuck and Europe '72. By then she was mixing the tapes herself. Also by that time, as we can see by her Betty Boards, she was often on the road with the band (she recorded the Academy of Music shows, for instance) - although she seems to have made the tapes for herself, more than for the band. One thing that happened in '72, she and Matthews split up - he was still on tour with them in late '72, but after that seems not to have been involved with taping. By '73, Betty was recording not only the Dead's shows, but Garcia's shows as well. (She'd also taken up with fellow crew-member Rex Jackson....) ~ Bear At The Board

The article later lists Bob Matthews as ‘Crew Chief’.

Rex Jackson

Speaking of Rex Jackson briefly, he was mentioned elsewhere in Bear at the Board:

I've talked elsewhere about the Dead's lamentable decision to stop taping themselves in 1970; but by 1971 they were recording every show again. Rex Jackson was the taper through much of 1971 (for instance, he taped the 10/31/71 show).

Rex Jackson passed away early on the Dead’s career, in 1976, and they founded a non-profit organization, the Rex Foundation in his memory. On, rexfoundation.org there is a history blurb:

From their earliest days, the Grateful Dead received countless requests for help from community organizations, and became known for their generosity and their numerous benefit concerts. In the fall of 1983, members of the band, with family and friends, established the Rex Foundation — named after Rex Jackson, a Grateful Dead roadie and later road manager until his untimely death in 1976 — as a non-profit charitable organization, allowing the band to proactively support creative endeavors in the arts, sciences, and education. The band played the first of many Rex Foundation benefit concerts in the spring of 1984.

Following Grateful Dead lead guitarist Jerry Garcia’s death in 1995 and the subsequent dissolution of the band, the Rex Foundation has continued to make grants funded by the very elements that hold our community together: music, connection, fun, creativity and community spirit. Since 1984 the Rex Foundation has granted $8.9 million to over 1,200 recipients.

Candace Brightman

So, there is one last loose end to tie up and then I think we will be out of time, I would like to talk about Candace Brightman. Earlier in the Dan Healy interview he gave her great accolades. She was the lighting director from the Dead. I have an article that describes her well, from PulseLighting:

If there's ever a concert lighting hall of fame, Candace will surely be among the first inductees. After launching her career in New York in the 1960s, she started out lighting shows at Madison Square Garden, the legendary Fillmore East and dozens of other arenas up and down the east coast. Her most notable work came from 1972 to 2004, When she served as Lighting Director for The Grateful Dead. With The Dead, she developed their shows into highly sophisticated visual spectacles, incorporating set design, automated lighting and video—technologies in which she is considered an industry pioneer. Most recently, she oversaw the design of Fare The Well, the band’s 50th anniversary show. Candace currently serves as a senior advisor and mentor to the Pulse Lighting Team.

So thats a little bit about Candice, if you want to hear more about her, there is a great podcast I found called: The Light Side. On Episode 7, they have Candice as a guest, and she talks a lot about the history of the Grateful Dead’s lighting. And, I personally dont know anything about lighting, as this is a music podcast. I am a music guy, but I really found it interesting.

Some of the stuff she talked about from 1972 was that they had to use different dimmers, and they had to wrap their lights in copper wiring because of the weird micing that they where doing in the early experimentations of the wall of sound, so you get to hear a little bit more of a technical aspect of that. She talks collaborating with the band and her lighting philosophy so definitely check out that episode of the light side if you are interested in Candice.

Conclusion

It looks like the clock is sort of running out, so I want to summarize everything we have been though, and it has by no means even close to everything I have to say about this Europe 72 album. It is such an interesting piece of music. But just to review the Liner notes again:

Note the familiar text at this point:

- Cumberland Blues

- Garcia / Hunter songwriting

- He's Gone (Lenny Hart & Mickey Harts absence)

- We heard parts of Brown Eyed Women and Tennessee Jed in the beginning

- The whole band was discussed

- Rex Jackson

- Kid Candelario

- Dan Healy

- Candice Brightman

- Betty Cantor

- Bob Matthews

- Wizard

- Sam Cutler

- John McIntire

- Rock Scully

- Alan Trist

- Alembic Sound (Absence of Owsley 'Bear' Stanley)

- Kelley / Mouse Studios

With that I will conclude this podcast. Like I said in the beginning this is such an interesting period for the Grateful Dead The Europe 72' era.

The really interesting thing to learn and to study about the Grateful Dead is that they are more than just a band and more than just an artistic collective. We did not even get past the artistic collective in this episode, but I wanted to show how differentiating just that part of the band is.

I had a note from Wiz, or Dan Healy which said

Each person in the Grateful Dead was given the reins to be a creative in their own right

This was the philosophy of the family, and the biggest take away of all of this. Try to build a team of crazy mad scientists and see where it goes!

This was 72 on 72: Volume 1.

I hope you enjoyed it, and I hope to have you back for Volume 2.